In the previous post, we left off with the tension between the Scientist (who wants to open the black box) and the Engineer (who wants to connect it). To understand how to bridge this gap, we first need to look at what they actually do all day.

1. Tools and Methods

Scientists: “I will investigate why you suck.”

Engineers: “I don’t care why, but I will quantify, to five decimal places, exactly how much you suck.” [1]

Despite their different philosophies, the tools and methods used by both sides are surprisingly similar.

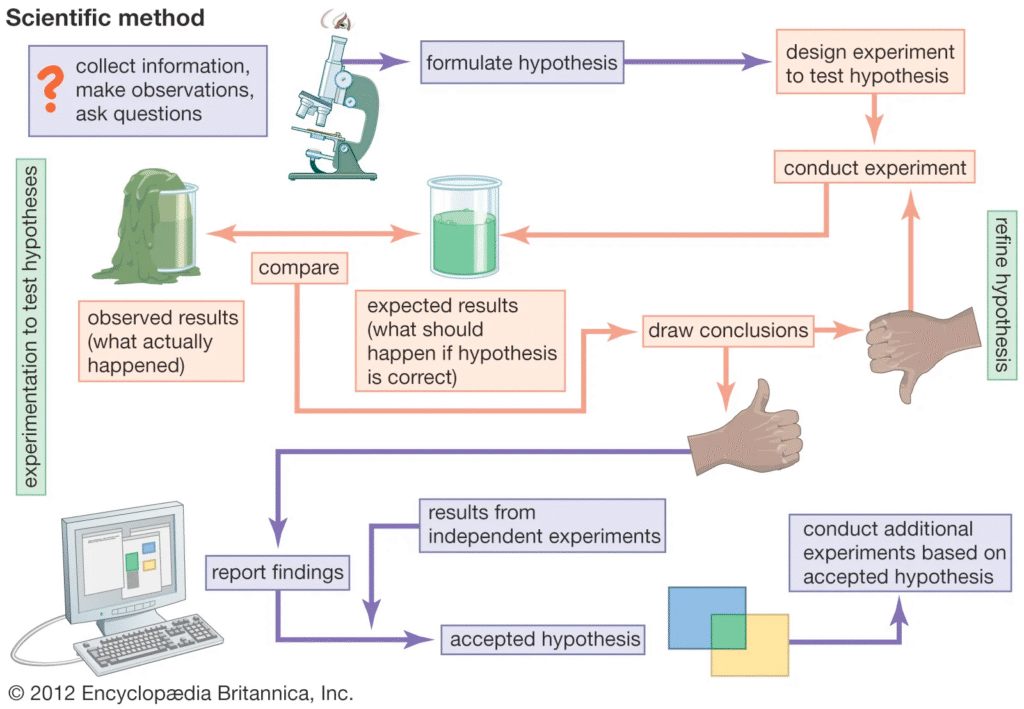

Investigating phenomena is a key part of the scientific process, but it is not the only one. Scientists also need to design experiments, build apparatuses, and develop methods to test their hypotheses. Very often—particularly in experimental physics—they are using engineering principles: reusing components, writing code, and optimizing procedures to verify their concrete predictions.

While every academic lab is full of potentially brilliant engineers, they are trained to discover new phenomena and look for novelty by pushing the boundaries of their setups. This mindset is universal for both theorists and experimentalists; just sophisticated lemmas and theorems are replaced by state-of-the-art experimental setups. Both share an “art-like” approach, relying on “tribal knowledge” passed down informally through generations of students.

For engineers, this tribal knowledge is simply codified. It takes the form of standards, best practices, and design patterns, allowing for easier transfer of knowledge between teams. Here, the common ground is the toolset; the difference is just how formalized the knowledge becomes.

2. Reality and Funding

Scientists look for funding. Engineers do paperwork. [2]

While both often receive fixed salaries, the source of that funding dictates their reality. This creates distinct working environments. Scientists in academia generally possess the freedom to explore, but face uncertainty and fierce competition for grants. Engineers in industry typically enjoy more resources and support, but face immense pressure to deliver specific results within rigid timeframes.

However, this situation shifts when we look at the scale of the project.

While the distinction above holds true for small projects, like a personal grant or a product iteration, it blurs in massive endeavors like a moon landing or building a quantum computer. In these cases, large budgets are dynamically shared between engineering and science, and everyone experiences the pressure of chasing a moving target.

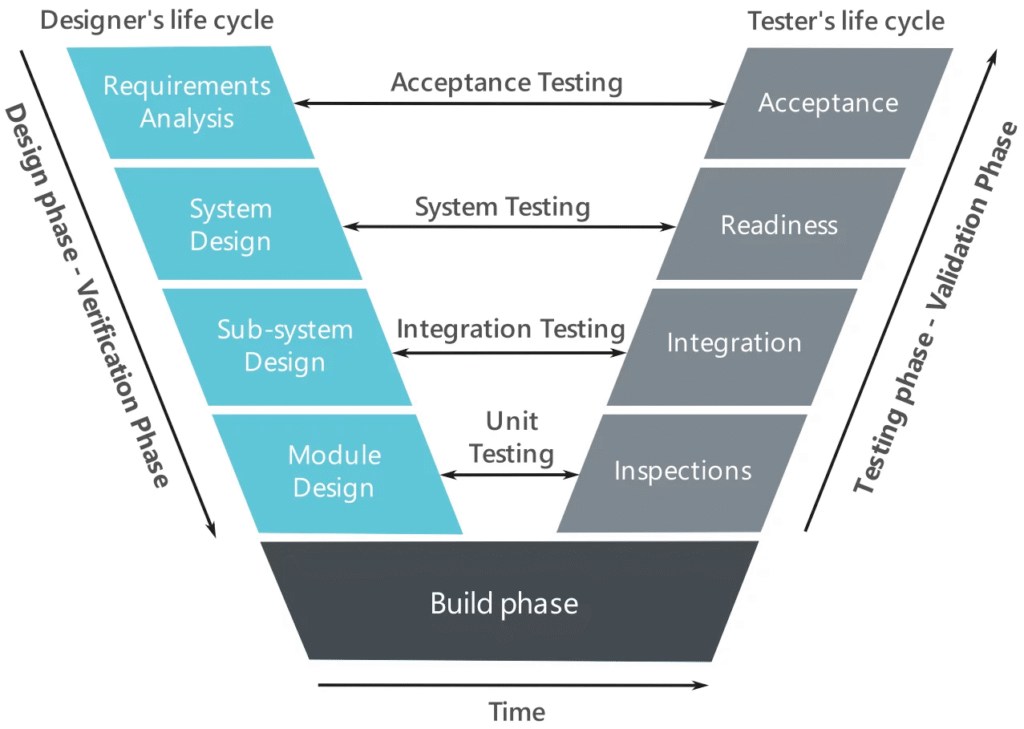

This requires decisions to be made on the fly, demanding a level of iteration that is uncomfortable for both pure scientists and pure engineers. While project managers deal with the well-defined logistics, they cannot solve the technical unknowns. To navigate the uncertainty and complexity of such projects, we need a more adaptive approach to planning and decision-making, one based on the self-consistent application of the scientific method to engineering tools.

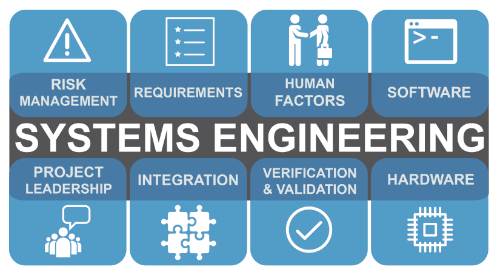

3. Systems Engineering – the bridge we need

While the scientist is interested in opening the black box, and the engineer aims to connect many boxes into a valuable product, interestingly enough, once sufficiently many and sufficiently complex “black boxes” are connected together, the system itself starts to develop its own input-output behavior, often with non-trivial emergent properties. Because these macroscopic behaviors (like non-linearities, cross-talk, and noise) arise from the interactions rather than the components themselves, a pure physicist’s reductionism isn’t enough. A hybrid approach is needed.

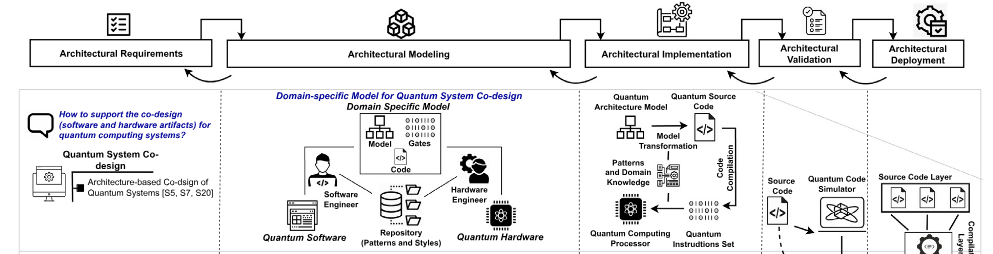

This is where Systems Engineering comes into play. It acts as a discipline that combines the scientific method of understanding phenomena with the engineering method of building and optimizing systems. Think of it as the science of engineering, or the engineering of science. Either way, it uses the tools of both disciplines to achieve a single goal: designing and optimizing complex systems that deliver value to society, even while working in high-uncertainty environments.

4. Quantum Engineering

Quantum computing is the place where principles of quantum mechanics are applied to build practical devices, with a keen eye on return on investment. It is like a… superposition of science and engineering (I cannot believe I wrote that, but ok)

In a classical chip company, the physics of the transistor is settled, allowing us to iterate purely on the engineering. In quantum computing, however, the qubit is very much a moving target. The physics is not fully understood, and we are still discovering new phenomena that impact performance. Yet, we are building prototypes—often with limited understanding of the underlying physics—and trying to optimize them to attract investment.

This creates a high-entropy environment where requirements change constantly. Delivering results here requires a discipline that can handle the rigor of engineering while tolerating the uncertainty of science. It demands a structured approach that understands trade-offs, yet retains the willingness to iterate as new information becomes available.

This sounds like a job for Quantum Systems Engineering. The field that already managed to disappear once, but is now coming back with a vengeance. More on this in the next post.

[1] https://www.science.org/content/article/what-heck-engineer-anyway

[2] https://www.reddit.com/r/AskEngineers/s/ZOxihDaVCk

[3] NASA definition of system engineering: https://www.nasa.gov/reference/2-0-fundamentals-of-systems-engineering/

[4] Application of systems engineering methods in real-life: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/you-should-really-learn-systems-engineering-even-can-apply-schneider/

[5] Nice summary of what SE is http://sysengr.engr.arizona.edu/whatis/whatis.html

[6] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2023.111682

[7] Matlab course on SE: https://www.mathworks.com/videos/systems-engineering-part-1-what-is-systems-engineering–1602837702185.html

Leave a Reply