In the previous post, we discussed the gap in Technological Readiness Levels (TRL), a “valley of death” that currently traps quantum devices in a region where funding is still mostly academic. I believe the best way to bridge this gap is to formulate a sufficiently meaningful challenge. Solving it would allow us to leapfrog the gap entirely. Here, I propose one such challenge, explain its motivation using a motorsport analogy, break down why it is so difficult, and suggest a potential path to solve it.

Hypercars vs Formula 1 philosophy

February is that time of year when Formula 1 fans emerge to predict the new season based on engineering rumors and regulatory loopholes. F1 cars are the ultimate “hero devices”—the fastest circuit-racing cars on Earth. But they are also impossibly fragile, complex, and designed to survive for only about two hours on a pristine track.

Interestingly, this sprint approach is exactly the opposite of how the automobile actually evolved.

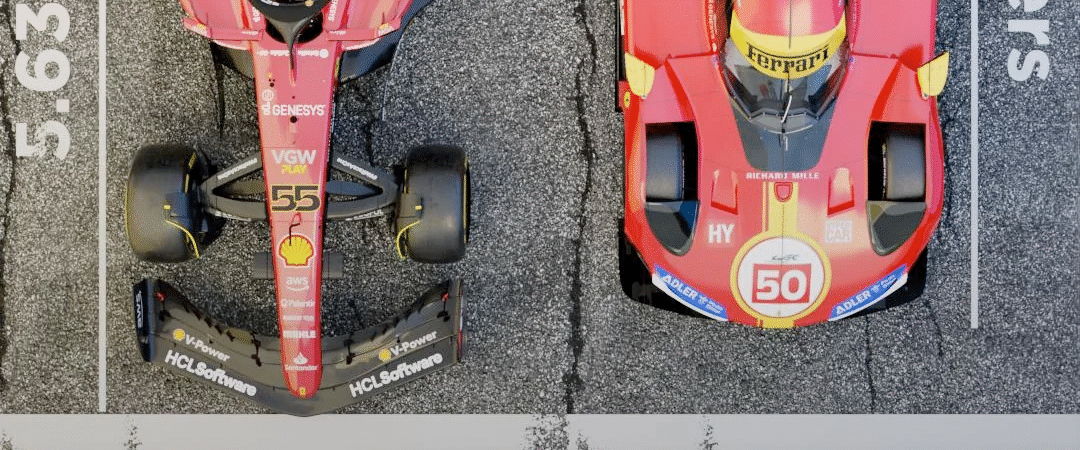

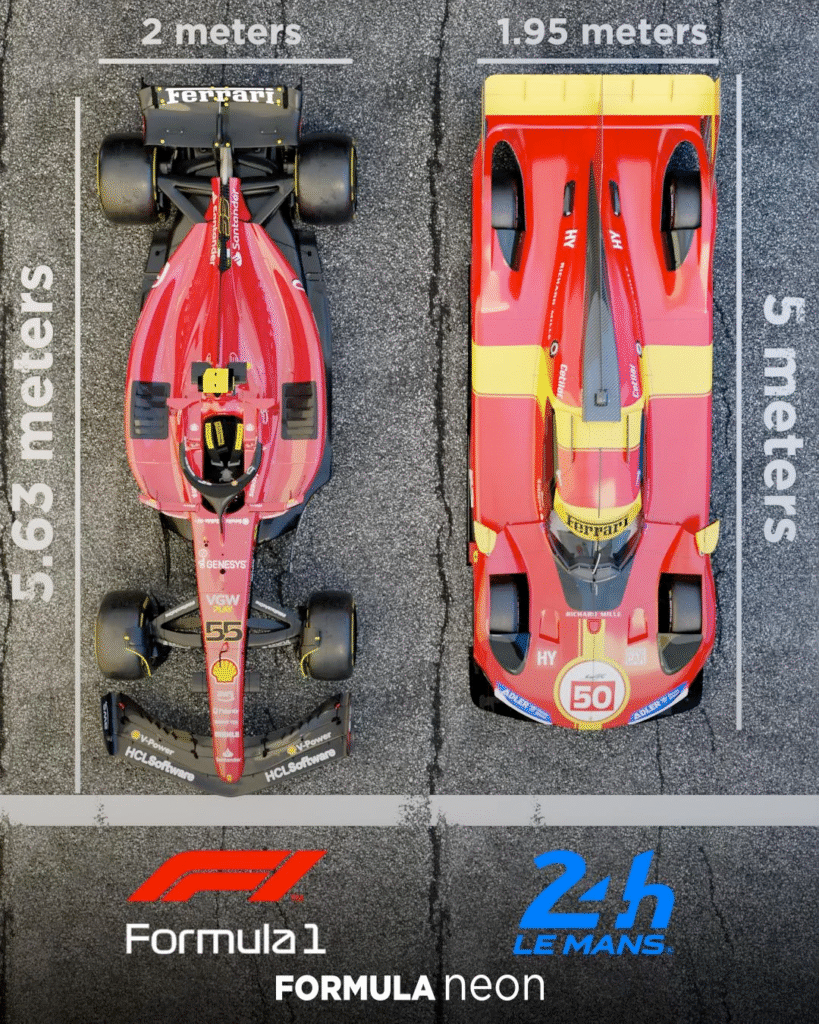

Historically, cars went from basic prototypes straight to scalability and endurance. Henry Ford revolutionized manufacturing through resilience. In motorsport, this endurance mindset birthed the 24 Hours of Le Mans, a brutal test of stamina for both man and machine (See Le Mans 66 the movie [1]). Even today, Le Mans Hypercars are massive, closed-cockpit machines built to survive 24 hours of abuse at 300 km/h. Instead of obsessing over microscopic design limits like F1, Hypercar regulations focus on measurable performance outcomes, a philosophy deeply aligned with true Systems Engineering. For differences between F1 car and hypercar see this thread [2], interview with 2009 F1 World Champion Jenson Button [3], and the animation at the bottom.

Quantum computing is currently doing this completely backward. We started by building F1-like quantum chips, hero devices that are fantastic for publishing papers in perfectly controlled labs, but terrible at long-term endurance. This is particularity true for semiconductor spin qubits, which pays for potential scalability with relatively more unpredictable environment that generates random electric and magnetic fields. If we want to leverage the semiconductor technology for quantum computing, we desperately need a “Hypercar” spin qubit. A standardized, resilient baseline is the only way to build a platform that actually scales.

That’s why I’m proposing Challenge 99/24 for spin qubits: Keep a two-qubit gate operational, meaning a fidelity above 99%, consistently for 24 hours.

Why this is difficult?

In a word: drift. Spin qubits suffer heavily from parameter drift caused by an ever-evolving environment, primarily 1/f charge noise in the semiconductor host. Most two-qubit gates rely on manipulating the electrically controlled exchange interaction, J. If we want to run a typical gate (like a CPHASE) where the target phase accumulation is π, any environmental fluctuation δJ directly translates to a phase error δϕ:

\delta \phi = 2\pi \delta J t

For small errors, the loss in fidelity ΔF scales quadratically:

\Delta F = \frac{\delta \phi^2}{2} = \frac{1}{2} \left(\pi \frac{\delta J}{J_0}\right)^2If you have an exchange coupling of 50 MHz, hitting your target phase takes a gate time of roughly 10 ns. If the J shifts by just 2 MHz, your phase error is about 0.13 radians, which translates to about 1%.

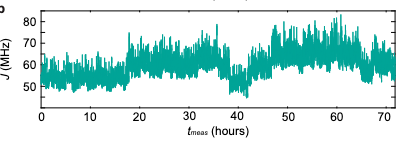

So, how much does the environment actually drift?

Even at smaller timescale, the expected drift is problematic. For the 1/f spectrum, which dominates those devices the typical drift depends on the waiting time as:

\delta J = \sqrt{A_J \ln(t/t_{shot})}Here, tshot is the timescale of a single experiment (typically 10μs), and AJ is the amplitude of the exchange noise. While the AJ depends entirely on your gate speed and typical noise amplitude. To run a fast 50 MHz gate, you must tune to AJ of roughly 0.35 MHz^2 (data consistent with [4]).

If we plug those numbers in, we find something terrifying: a 1.5-2 MHz drift—enough to instantly kill 1% of your fidelity—is expected to accumulate in just 2 to 3 seconds

The Pit Stop: Digital Twins and Real-Time Telemetry

To survive a 24-hour endurance race, you need to know exactly when to pull off for a calibration “pit stop.” And that requires a predictive understanding of your machine.

Let’s look at F1 one last time. Modern teams don’t guess their car setups. They rely on massive simulators running 24/7, testing countless tracks, tires, and weather conditions. Test drivers translate that digital data into physical reality. When a team arrives at the track, they use limited practice laps to gather live telemetry, allowing them to “zoom in” on the exact simulator data that matches the current track conditions.

We need to replicate this approach for semiconductor qubits. We need a digital twin—a hierarchical model acting as full-stack middleware. Imagine a system that takes a user’s quantum algorithm and automatically translates it into an optimization task, constrained and guided by real-time telemetry read directly from the qubit. But building a perfectly correlated simulator for a fragile quantum system is a monumental challenge. It requires completely rethinking how we model these devices.

In the next post, we will look at the example of such effective simulator, that deals with quantum error correction in presence of a drift.

[1] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1950186/

[2] https://www.reddit.com/r/wec/comments/1dv6igb/hypercargtp_or_f1_which_one_is_technically/

[3] https://www.planetf1.com/news/jenson-button-f1-not-as-technologically-advanced-wec

[4] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-28519-x

[5] https://www.reddit.com/r/wec/comments/18x3kfn/f1_vs_le_mans_hyper_car_size_comparison/

@formula.addict The difference between Hypercar and F1 🧐

♬ original sound – formula.addict